In neuroscience, creativity is defined as the ability to produce original and relevant ideas in a given context, to solve a problem or improve a situation.

What is creativity?

The most recent data, obtained mainly from functional MRI, indicate that creativity depends on connectivity between several regions of the brain and relies on interactions between several brain networks. There are two main networks. The first, the executive control network, is usually involved in cognitive control processes that enable us to exercise control over our thoughts, actions and behaviors according to our objectives. The second network is generally called the ‘default network’, and is thought to be involved in spontaneous cognition, such as when we make associations between ideas when our thoughts wander. The second network is thought to play a role in the spontaneous generation of ideas, by association, while the executive control network makes it possible to restrict the search for ideas, to manipulate them mentally and to inhibit ideas that are not interesting and select ones that are.

Evaluating creativity

There are three main approaches, or rather three categories of tasks that can assess individuals’ creativity. These tasks are also used to explore the brain’s basis for creativity in neuroimaging.

The most commonly used set of tasks are ‘divergent thinking’ tasks, in which participants are asked to give as many unusual ideas as possible. For example, there is the ‘alternative uses’ task, where a person is asked how they might use a common object such as a pen or paperclip. The number of ideas suggested within a given time is then examined, as well as the extent to which those ideas are original, that is to say ideas that are less commonly mentioned by participants.

A second approach, ‘associative combinations’, stems from a 1960s theory that defines creativity as the ability to combine things together that are not usually associated with each other. In other words, to create new associations and combinations. This capacity is thought to be linked, in part, to the fluidity and flexibility of how we organize our knowledge in semantic memory and how we store our knowledge about the world (objects, concepts, situations, etc.). The task is to suggest three words to a participant, who must find one word that can be related to each of the three. For example, ‘bread’, ‘crop’, and ‘grain’ are associated with the word ‘wheat’.

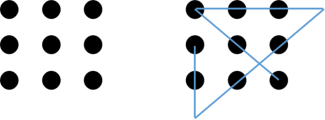

A third approach is to suggest problems to be solved. One of the best known is the ‘nine dots’ problem (see below), where you have to connect all the dots by drawing four straight segments without lifting the pen. To solve this problem, we have to move away from the implicit square that we imagine and draw segments that show that we are literally thinking ‘outside the box’.

This type of problem studies a person’s ability to resolve an impasse, to change perspectives and restructure how we have mentally conceptualized a problem in order to consider possible responses other than those that come to mind automatically and immediately.

At Paris Brain Institute

Emmanuelle Volle’s team focuses on creative processes. Using a functional MRI morphometric method, the team identified several regions of the brain that vary in structure or activity, depending on the individuals’ creativity.

Aside from numerous cognitive training protocols aimed at increasing creativity, which have been published but which have yet to be reinforced by scientific evidence and transferred to real-life scenarios, there are factors that can undoubtedly be influenced in a person’s everyday life.

This is often referred to as ‘incubation’. This is the period between reaching an impasse in a problem’s resolution and the time when a solution to the problem emerges while we are doing something else. This phase is called ‘incubation’ because it is thought that during this phase when we’re not seeking to resolve the problem there are still things occurring that do encourage a eureka moment. Researchers have studied this phase and demonstrated that, in most studies, this incubation phase was beneficial, and even more so if the person was performing a task as opposed to doing nothing.

Isabelle Arnulf’s team (AP-HP/Sorbonne University) is studying how sleep influences creativity. People with narcolepsy, who have enhanced access to REM sleep, benefit from greater creativity. This suggests a link between this specific phase of sleep, REM sleep, and creative capacity. Very recently, the team’s researchers have found that there could be another phase conducive to creativity at the point of falling asleep. Activating it requires us to find the right balance between falling asleep quickly and not falling asleep too deeply. These ‘creative naps’ could offer an easy and accessible way of stimulating our creativity in everyday life.

The goal of the Frontlab team is to understand better the role and organization of the prefrontal cortex in the control, activation, and inhibition of goal-directed behaviours.

Read more

The team aims to discover why we sleep and dream and understand the mechanisms of neurological sleep disorders to treat them better. Both clinical and basic research axes investigate hybrid states between wake and sleep, using neurophysiological...

Read more