Dystonia can have a number of causes, a genetic mutation and side effect of a medication such as an antipsychotic or an anti-nausea drug Another neurological disorder or a severe lack of oxygen to the brain.

Causes of Dystonia

Generalized dystonias are usually genetic, hereditary, and therefore familial, or caused by a new mutation in the patient’s DNA (sporadic cases).

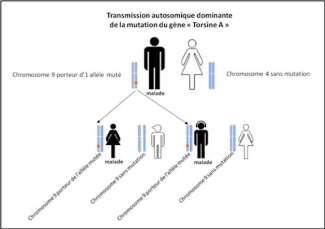

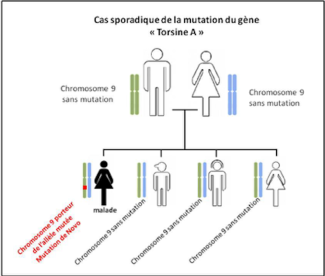

Primary generalized dystonia, also known as idiopathic torsion dystonia, begins in childhood and is caused by a mutation in the DYT1 gene (chromosome 9) that encodes the protein TORSIN A. The function of this protein in the brain is not yet fully understood, but it may interact with dopamine, a neurotransmitter that enables communication between neurons.

The DYT1 gene mutation is transmitted in an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning that a single allele of the mutated gene is sufficient to cause the disease.

There are also sporadic cases, involving patients with no family history but who carry the mutation.

Dopamine-responsive dystonia is also rare and hereditary (autosomal dominant transmission). It is characterized by an improvement in symptoms when the patient is treated with a dopamine derivative.

Focal or segmental dystonia can have several non-genetic causes.

They can result, for example, from a severe lack of oxygen (hypoxia) in the brain at birth or following a stroke, trauma, or anatomical brain abnormalities. They can therefore appear at any age depending on their cause.

Other neurological disorders such as multiple sclerosis or Wilson’s disease (copper build-up in cells) can also cause symptoms of involuntary muscle contractions similar to dystonia.

Finally, certain anti-nausea or antipsychotic medications can cause the onset of dystonia.

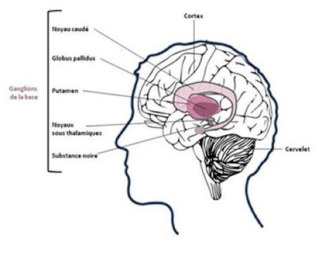

Whether idiopathic, hereditary, or acquired, whether generalized or not, dystonia results from a dysfunction of neural circuits and impaired communication between several brain regions involved in motor control: the basal ganglia, the cortex (peripheral gray matter of the brain), and the cerebellum. Hyperactivity – the excessive and chaotic communication between these structures – appears to be the cause of the dystonia symptoms observed in patients.

The basal ganglia are regions of the brain that initiate and coordinate voluntary muscle movements and suppress involuntary movements.

The cerebellum contributes to the coordination and synchronization of movements and to the precision of these movements.

At Paris Brain Institute

The research objectives of the MOV’IT: Movement, Investigation, Therapeutics. Normal and Abnormal Motor Control: Movement Disorders and Experimental Therapeutics team on dystonia led by Prof. Marie Vidailhet and Prof. Stéphane Lehéricy are to restore brain function, allowing the patient to regain optimal motor control and overall well-being. To achieve this, the team is developing multimodal research in imaging, neurophysiology, and clinical practice to understand the brain dysfunctions that cause dystonia and develop solutions to repair them. The team has demonstrated significant involvement of the cerebellum, which has the ability to both compensate for and alter movement.

A recent study by the MOV’IT team, led by Yulia Worbe (AP-HP/Sorbonne University), Emmanuel Roze (AP-HP/Sorbonne University), Pierre Pouget (CNRS), and Clément Tarrano (AP-HP/Sorbonne University), shows that visual signal integration is impaired in patients with myoclonic dystonia.