Memory is a valued building block of our autonomy. Here are some key facts about it!

Memory is our ability to record, store and retrieve information. It helps us retain knowledge, recollections and day-to-day actions. Thanks to memory, we can remember a phone number, a lesson, a face, or how to ride a bike. As the epicenter of everything we remember, learn and know, memory helps us to interact with our environment and adapt to it, and to learn and guide our thoughts and decisions. It also helps us to live in the present and anticipate the future, based on our past experiences, and to build our identity. This means it is vital to our autonomy. If it malfunctions, it affects our whole life.

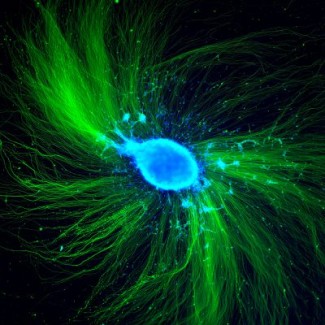

Contrary to the idea that memory is simply a safe for storing information, it actually operates like a dynamic network in which different types of memories interact.

Short-term memories

- Sensory memory automatically records, very briefly and unconsciously, information we receive from our senses (hearing, smell, vision). It is thanks to sensory memory that we can instantly recognize a voice, a familiar face, or the taste of a food.

- Working memory, meanwhile, makes it possible to temporarily hold information in mind and manipulate it for a few seconds. It is used to remember a telephone number while dialling it, or to do a mental calculation.

Long-term memories

- Semantic memory is our memory of facts and general knowledge. Thanks to semantic memory, we know that Paris is the capital of France, what a tree is, and how the rules of grammar work.

- Episodic memory allows us to store and retrieve a memory of an event, including events in our own past, in their specific context (where, when and how it happened).

- Implicit memory refers to learning that is automatically activated without conscious effort. This includes, for example, procedural memory, which is our memory of skills and tasks we have learned, such cycling or playing the piano.

Functional brain imaging has revealed that our memory systems rely on separate but interconnected regions of the brain. Sensory memory therefore relies on sensory areas that receive stimuli from the sensory organs (eyes, ears, nose, fingers); working memory mainly uses the prefrontal cortex, located at the forehead, also involved in managing information in real time and in decision-making; semantic memory uses the parietal lobes (at the back of the cranial vault) and temporal lobes (at the temples), which are responsible for storing general knowledge and language; episodic memory depends on a network involving the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus that links together different information (place, emotions, sensory perceptions) to form a coherent memory; while implicit memory involves structures nestled deep in the brain.

To be able to function well, the different forms of memory don’t just interact with each other. They are also deeply linked to the senses, to emotions, and to language and movement control.

As we age, the brain undergoes changes that alter how memory works. Neurons become smaller, and their communication slows down, while some synaptic connections also get weaker. We then find that learning to use something new, or recalling a person’s first name, can take longer. However, in the normal ageing process, when the brain is not affected by a condition, creating new memories or remembering the past is still perfectly possible. Long-term knowledge (semantic memory), learned skills (procedural memory) and old recollections (autobiographical memory) are not affected.

However, if the brain is affected by a condition, memory disorders are much more pronounced and affect specific skills. In Alzheimer’s disease, for example, there is an abnormal accumulation of toxic proteins, which results in progressive neuron loss. Because the hippocampus is particularly affected, the first symptoms include episodic memory problems: at first, the person has difficulty storing new information, even after several repetitions, and in creating new memories. Later on, they will also begin to lose older memories.

Other conditions can affect memory in different ways. Frontotemporal dementias affect working memory, causing difficulties in organizing memories and retrieving them in a coherent way. In some cases, the patient gradually loses their ability to understand the meaning of words and concepts (semantic dementia).

At Paris Brain Institute, two teams carry out research into memory. The ‘Frontal Functions and Pathologies’ (FRONTLAB) group investigates the role and organization of the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that hosts the different ‘superior’ cognitive functions, including working memory. The ‘Alzheimer’s Disease and Prion Diseases’ team, meanwhile, studies the molecular mechanisms involved in the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease, among other conditions. In the long term, this research could help to develop potential treatments to prevent the development of this condition, which currently has no cure.

Alzheimer's disease

With longer life expectancies and the biological mechanisms at the origin of neurodegenerative diseases becoming increasingly complex, it is now estimated that, in France in 2020, 1.3 million people were affected by Alzheimer’s disease. Today, more...

Read moreThe goal of the Frontlab team is to understand better the role and organization of the prefrontal cortex in the control, activation, and inhibition of goal-directed behaviours.

Read more