Tourette’s syndrome, like many other neurological diseases, has a genetic component. Though it is not hereditary, a patient’s relatives have a genetic predisposition that increases the risk of developing the disease.

The biological mechanisms of Tourette’s syndrome

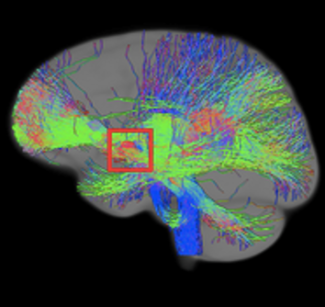

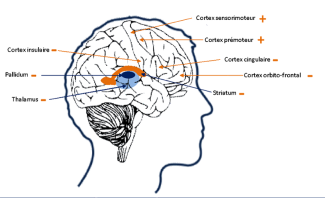

The specific mechanisms behind the symptoms of Tourette’s syndrome are still not fully understood. What we do know is that brain networks connecting the cerebral cortex to deep structures known as basal ganglia play a key role in causing tics and other related symptoms.

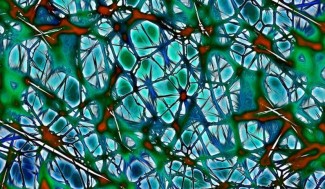

Recently, a histological analysis by the team at Yale University suggested that anomalies observed may indicate a disruption in GABAergic interneuron migration in the striatum, a key structure of the basal ganglia. The striatum plays a central role in relaying cortical information and helping to select the most appropriate action for a given situation. GABAergic interneurons, absent or dysfunctional in this region, are essential to the synaptic integration of cortical information, influencing the precision of interactions between sensation and action.

A study at Paris Brain Institute by Professor Yulia Worbe and her colleagues on the Mov’It team used advanced computer analysis methods to explore resting brain connectivity in people with Tourette’s syndrome. The results revealed significant differences in brain networks, including in the striatum, the cerebellum and the insular cortex, distinguishing Tourette’s syndrome patients from patients who do not have the condition. The analysis also showed that patients undergoing treatment have different brain connections to those of untreated patients, particularly between the caudate nucleus (part of the striatum) and insular cortex. This work highlights the key role of brain networks in this syndrome and opens up prospects for using brain imaging to improve diagnosis and more accurately assess treatment effectiveness.

At Paris Brain Institute

Research into patients with sudden bouts of verbal and physical aggression has highlighted, using functional MRI, a decrease in connections within the orbitofrontal cortex and dysfunctional connectivity between the orbitofrontal cortex, the amygdala and the hippocampus. This study concludes that these sudden ‘outbursts’ result from ineffective control over actions and dysfunction in emotional regulation and impulsivity.

• In a study published in the journal Brain, Yulia Worbe and her colleagues (’Mov’It :Movement, Investigations, Therapeutics. Normal and Abnormal Motor Control: Movement Disorders and Experimental Therapeutics’ team, led by Professors Vidailhet and Lehericy) showed that patients with Tourette’s syndrome develop more habitual behaviors than healthy subjects of the same age.

These findings shed new light on the mechanisms that explain why tics happen and why they continue. For example, they could be partially learned actions that become automatic and persist in the same way as bad habits. Problems in neuronal networks involved in habit-forming could explain why these behaviors are exacerbated in patients.