Tourette’s syndrome (TS) was first identified in the 19th century by French neurologist Georges Gilles de la Tourette. It is a neuropsychiatric disorder with a genetic component characterised by sudden, brief and intermittent movements (motor tics) or vocalisations (auditory tics). Tics appear in childhood, generally between the ages of 6 and 8, and are almost always (in 85% of cases) subsequently combined with one or more psychiatric disorders: attention deficit disorders with or without hyperactivity, obsessive-compulsive disorders, rage, autism spectrum disorders and learning disorders.

-

0.5 % de la population française est touchée

-

85 % des cas sont associés à un ou plusieurs troubles

In France, Tourette’s syndrome affects around 1 in 200 people (around 0.5% of the population), and it is more common in boys than girls.

Another feature of this syndrome is that it resolves or spontaneously improves in adulthood in around 75% of patients. For the remaining 25% of patients, symptoms may persist or even worsen. One of the challenges in this condition is therefore to try and understand why some patients spontaneously improve, so that we can develop therapeutic strategies to help the others.

Biological mechanisms and causes of Tourette’s syndrome

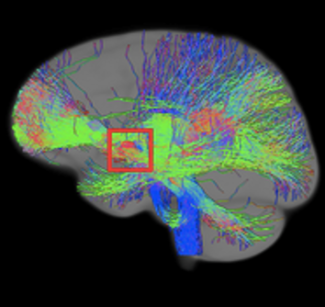

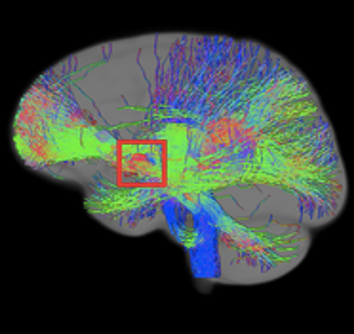

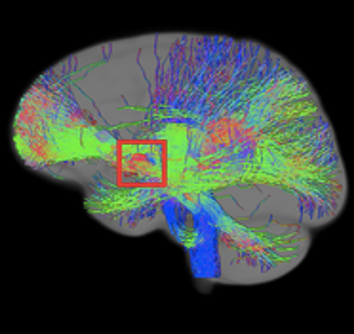

The precise mechanisms that cause the symptoms of Tourette’s syndrome are still poorly understood, but the basal ganglia or central grey matter, deep structures in our brain, are specific areas involved in the generation of tics. Research at Paris Brain Institute aims to pinpoint the brain regions responsible for the symptoms in order to customise therapies.

There is a genetic component to TS, but few predisposing genes have been identified so far. The risk of developing the disease is higher for a patient’s relatives than for the general population. There are probably also environmental risk factors that have not yet been identified, so we are therefore dealing with a multifactorial syndrome. Teams at Paris Brain Institute are members of international genetics consortia that are conducting large-scale research to identify the genetic variants associated with this syndrome.

Symptoms of Tourette’s syndrome

Symptoms of Tourette’s syndrome typically include a combination of motor and vocal tics lasting for more than a year in an individual under the age of 18, according to the DSM-5 criteria. Tics vary greatly from one individual to another. Motor tics generally appear first, and mainly affect the upper body, face, head and arms. They may then be followed by vocal tics. Coprolalia, often the subject of caricature and involving the repetitive uttering of insults, occurs in fewer than 20% of patients with Tourette’s syndrome.

The psychiatric symptoms associated with Tourette’s syndrome are mainly attention deficit disorder, with or without hyperactivity, obsessive-compulsive disorders and autism spectrum disorder.

Diagnosis of Tourette’s syndrome

Tourette’s syndrome is diagnosed on the basis of an evaluation of the patient’s symptoms through clinical examination only. Additional examinations such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or electroencephalograms are rarely necessary, and are only conducted to rule out other pathologies. A tic frequency and intensity rating scale (Yale Global Tic Severity Scale, YGTSS) is used to measure the severity of the disease. Researching diagnostic and prognostic markers for this disease is a key challenge for researchers and clinicians at Paris Brain Institute.

Treatments for Tourette’s syndrome

Tourette’s syndrome can be treated in a number of ways, depending on the patient’s clinical profile and the severity of the tics. Behavioural psychotherapies aimed at addressing the tics are the first-line treatment according to European and US recommendations. These are suitable for all patients, regardless of the severity of their tics, but require regular exercises over a period of several months. At present, this type therapy is often not feasible due to a lack of trained professionals. Drug-based treatments, primarily neuroleptics, are therefore used as an alternative for improving a patient’s day-to-day life and their integration into school or the workplace. Regular psychotherapy, speech therapy and psychomotor therapy are also recommended, depending on the patient’s specific symptoms. Finally, deep brain stimulation can be offered in the most severe cases that are resistant to behavioural therapies and medication.

Support Paris Brain Institute

Did you like this content and did it answer the questions you were asking? Don't hesitate to support Paris Brain Institute.