Alzheimer’s disease is often known for the memory loss experienced by patients. It is a progressive disease that usually begins with an amnesiac syndrome that is isolated, progressive and unknown to the patient. Progressively, there are problems with language (aphasia), writing (dysgraphy), movement (apraxia), and loss of the ability to recognize objects and faces (agnosia).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is based on:

- A clinical examination to assess cognitive function and behaviour through specific tests.

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) visualizes a loss of volume in the hippocampus, the area of the brain essential for memory, and/or other areas of the brain

- PET (Positron Emission Tomography) with glucose that visualizes brain metabolism during disease

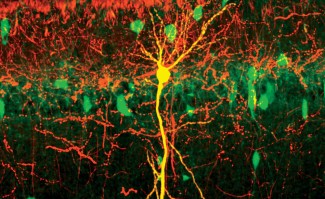

- The analysis of CSF (Cephalo-Rachidian Liquid) circulating around the brain and in the central spinal cord canal, obtained by lumbar puncture. Changes in the concentration of two dosage molecules in this fluid, amyloid protein and tau protein, are characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease.

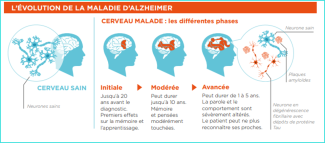

It is traditional for doctors and researchers to distinguish four stages in Alzheimer’s disease:

- Stage of Mild Cognitive Impairment: Symptoms such as memory impairment are measurable but have little or no impact on everyday life.

- The so-called ‘mild dementia’ stage. Dementia is a medical term that simply means that the symptoms affect the autonomy of the patient, who needs help with at least one significant task in his/her day-to-day life that he/she used to do alone (e.g. paying bills). It therefore has a different meaning from the term dementia used in everyday language. At this stage, the symptoms are more marked than initially and begin to handicap the patient. The disease may also have begun to spread and affect other functions such as behaviour, language and vision, in addition to greater memory loss. Patients need help with some daily activities.

- The so-called ‘moderate dementia’ stage. At this stage the disease has spread and more clearly affects other cognitive functions as well as greater memory loss. At this stage, patients need help with several daily activities.

- The so-called “severe dementia” stage: Short- and long-term memory is severely impaired. The rest of the cognitive functions are also severely affected. Patients are no longer independent in their daily lives and need help with basic tasks.

Today, there is no effective treatment to stop the progression of Alzheimer’s disease or to cure it. Knowledge of its mechanisms is still very limited. We know that biomarkers can be used to identify the disease before the first clinical signs appear, for example through recently identified potential blood markers, but early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s remains difficult for practitioners. And when symptoms do occur, patients have been affected for several years, it is often too late to act effectively to stop Alzheimer’s progression. Research into Alzheimer’s disease and its upstream phase is therefore essential in order to intervene as early as possible and be able to develop new treatments.

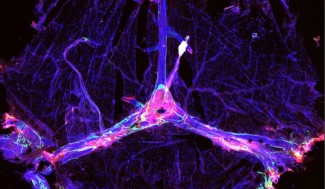

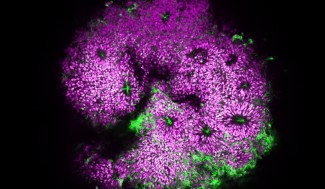

The INSIGHT cohort, followed at the Institute for Memory and Alzheimer’s Disease by Dr. Bruno Dubois’s clinical research team, is one of the first in the world to follow nearly 320 healthy individuals at risk in order to identify the triggers of Alzheimer’s disease. The first results of this study, published in early 2018, show, at 30 months of follow-up, that the presence of amyloid lesions has no impact on the cognition and behaviour of subjects who carry them. They suggest the existence of compensatory mechanisms in subjects with these lesions. However, all subjects who showed signs of Alzheimer’s disease during follow-up had these lesions. This cohort allows Brain Institute researchers to develop studies aimed at identifying brain “abnormalities” predictive of Alzheimer’s disease, that is, brain dysfunctions more than 10 years before symptoms appear and Alzheimer’s disease is diagnosed.

At Paris Brain Institute

Diagnosing Alzheimer's Disease in the Preclinical Phase with Electroencephalography

Sinead Gaubert, neurologist and researcher at Paris Brain Institute (CNRS/Inserm/Sorbonne Université) at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Federico Raimondo (Université de Liège/Sorbonne Université) and Stéphane Epelbaum, neurologist demonstrated early brain electrical changes in subjects in the preclinical phase of Alzheimer’s disease in the INSIGHT-preAD cohort using electroencephalography (EEG). could be used in future years to screen early for pre-clinical Alzheimer’s disease.

Identify patterns of disease progression

At Paris Brain Institute, Lara Migliaccio’s group on Richard Lévy’s team is studying vulnerability and resilience to disease, particularly in young subjects, and the extent to which functional neural networks respond to pathological impairment. The objective is to understand what steers the patient towards a pathology that is rather focal and less evolutionary or very diffuse with a much more severe evolution, and to identify the individual characteristics of the subjects that play a role in the disease, such as quality of sleep, lifestyle, diet, more or less intellectual activities, in order to obtain an individual-level measure of what is called cognitive reserve. The challenge of the project is to follow the patients possibly over several years and to highlight the baseline characteristics that predict the evolution at two years and extract concrete measures to build an algorithm of the personalized evolution of the patients.