Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) affects 2%-3% of the population. Symptoms typically appear around the age of 20 (or 14 in 25% of cases), in the form of repeated, persistent, unwanted and often anxiety-provoking ideas or images. These obsessions are often accompanied by repetitive behaviors designed to neutralize the anxiety and anguish resulting from the obsessions, known as compulsions. OCD is considered to be a disease of behavior, thought and emotion. Around a third of patients with OCD have also had – or still have – tics.

Psychological Mechanisms of OCD

The psychological mechanisms behind OCD are fairly well understood and identified. Most obsessive-compulsive behaviors are linked to irrational fears about danger or risk to oneself or those around us. The notion of responsibility or even guilt for what might happen is ever-present in patients. They are too invested in their own safety and that of others.

These fears lead to recurrent, unwanted and highly anxiety-provoking obsessions, thoughts or images in the patient, most of which concern the dramatic consequences of possible errors in the patient’s behavior or actions in terms of accident or death.

Most OCD patients are aware that their obsessions are unrealistic but are unable to escape them.

Compulsive Ritual Mechanisms in OCD

To alleviate or even eliminate these obsessions, patients develop compulsive rituals that must be performed in a specific manner. The irrational fear of contamination by viruses or bacteria, for example, can lead to excessive repetitive behaviors in OCD, such as washing one’s hands for at least two hours a day or showering according to a very specific protocol, such as soaping each armpit 17 times or each foot 20 times, starting with the right foot, and repeating the ritual from the beginning if a mistake is made or if the count is lost.

These rituals can cause patients to devote more than eight hours a day to such actions, leading to social withdrawal, job loss, and suffering for those around them.

Working, eating, and meeting other people become very difficult activities. If we take driving a car, for example, some patients have to retrace their route 20 times to make sure they haven’t killed anyone on the way, and then check multiple media outlets for several days to confirm that no accidents occurred while they were driving about.

Again, as with obsessions, most patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are aware that they will not die from infection if they do not wash their armpits 17 times, but they cannot break free from the need to perform these rituals in order to calm their anxiety and fear.

These obsessive-compulsive behaviors trap patients in a vicious cycle: obsession leads to a ritual, which, once performed, generates new obsessions.

From a more scientific perspective, this behavioral dysfunction appears to stem from what researchers call “pervasive doubts”, which are probably due to a breakdown in the control of the uncertainty involved in decision-making.

At Paris Brain Institute

The Neurophysiology of Repetitive Behaviors team, led by CNRS researcher Eric Burguière, aims to identify the brain dysfunction that causes pathological doubt and to understand why and how repetitive behaviors appear and become “automated”.

Using a translational approach in experimental models and OCD patients, and using brain imaging, the team’s researchers have demonstrated the essential role of two brain regions in this pathology.

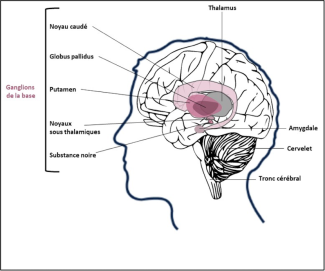

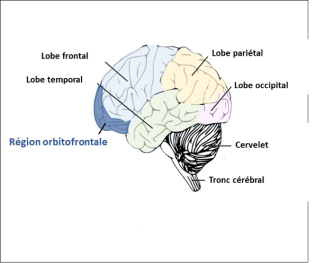

The orbital-frontal region is involved in the development of the pervasive doubt that causes repetitive checking behavior, while deeper brain regions called “basal ganglia” are more involved in managing emotions.

The objective of this research team is also to understand how the activity of neurons in these regions is disrupted in obsessive-compulsive disorders.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) findings, researchers have shown that neuronal activity in these areas of the brain is greatly increased in OCD patients.

fMRI is a brain imaging technique that measures the activity of neurons in areas of the brain that are active when a person performs a task such as reading, moving a limb, or looking at images, by measuring the increase in blood flow in these areas.

MEG can also be used to measure brain activity while a task is being performed by measuring the electromagnetic field emitted by active neurons.

One hypothesis to explain this hyperactivation of these brain regions is based on a disruption in the levels of neurotransmitters (molecules essential for the transmission of information from one neuron to another), such as serotonin, dopamine, and vasopressin.