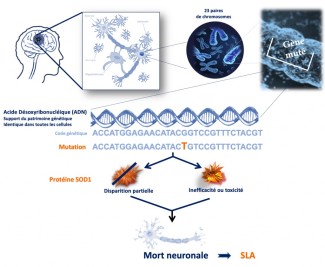

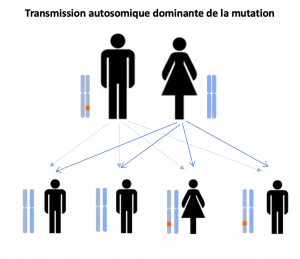

Ten percent of ALS cases are genetic in origin, while 90% are sporadic cases, i.e. cases with no identified origin. Identifying mutations is essential in orderto fully understand the mechanisms of the disease and to include patients inany therapeutic trials targeting some of the ALS genes.

Causes of Charcot's disease

To date, four major genes have been identified as responsible for more than 50% of genetic cases of ALS. Over 30 genes have been implicated in familial forms of ALS.

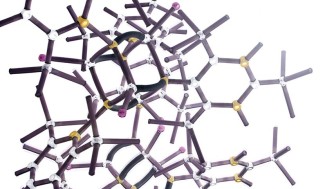

The superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) gene was identified in 1993, and so far more

than 150 different mutations have been found in patients. Since then, mutations have been identified in the TARDBP, FUS and C9ORF72 genes, the genes involved in RNA metabolism (TARDBP and FUS) and in immune response (C9orf72). However, these mutations do not automatically lead to loss of gene function, and this makes the research even more complex.

Today, more than 70% of familial cases are linked to a known mutation, and there is ongoing research to find the mutations responsible for the remaining 30% of familial cases.

In sporadic forms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), which account for 90% of cases, there are probably genetic variants that make certain people predisposed. In other words, there are genetic factors that increase these people’s risk of developing the disease. ALS is considered a multifactorial disease, and certain environmental or lifestyle factors may also contribute to the disease onset in predisposed individuals. So far, neither genetic factors nor environmental factors have been definitively identified.

Does environment play a role in sporadic cases of the disease?

Studies have been conducted into the influence of environmental factors. For example, in the 1950s, there were a large number of cases of a particular form of ALS on the island of Guam. These cases were attributed to a toxin present in microalgae that colonized seeds eaten by bats, which were in turn eaten by the island’s inhabitants! There have also been several cases of ALS among US military personnel returning from the Gulf War. Certain toxic products are suspected but have not yet been identified. Finally, the risk of a diagnosis of ALS is believed to be higher in certain athletes, including footballers and rugby players. There are many different potential theories to explain this, including pesticides, impacts while practicing these sports, and a motor neuron predisposition in these high-level athletes. These studies have been valuable for raising the question of environmental factors, and sporadic cases of ALS could well stem from a combination of several factors.

At Paris Brain Institute

Identifying new genetic mutations that cause ALS

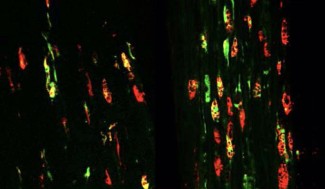

Stéphanie Millecamps, working in Séverine Boillée’s team, is conducting research to identify the genetic mutations that cause ALS. By working with the different specialist ALS centers in France, researchers were able to research genetic mutations in 400 families affected by ALS, and identify the genetic cause of the disease in 70% of cases. These studies make it possible to offer a molecular diagnosis to families who wish to have one, but also to include patients carrying a specific mutation in adapted clinical trials. Thirty percent of familial cases are yet to be linked to causal mutations, and large-scale genetic analysis methods are being developed to achieve this.

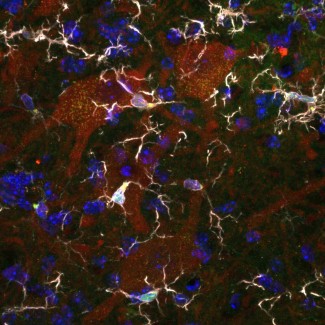

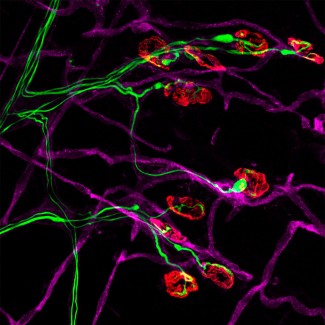

Collaborative work within Europe has identified a new gene involved in ALS. The gene, known as TBK1, is involved in waste elimination inside cells and in regulating inflammation. This demonstrates the importance of immune cells at disease onset, and probably also disease progression. Christian Lobsiger, working in Séverine Boillée’s team (in partnership with a German team), is modelling ALS linked to mutations in the TBK1 gene to study these mechanisms and gain a better understanding of the disease.

Isabelle Le Ber, working in Alexandra Durr and Giovanni Stevanin’s team, took part in an international study that in 2018 identified a new causal gene in ALS – the KIF5A protein, which was already involved in another central motor neuron condition: spastic paraplegia.