The symptoms of epilepsy are the clinical signs described by the patient themselves and by those around them during a seizure. The clinical signs depend on the brain region affected by the abnormal electrical activity (epileptogenic focus) and the size of the affected brain area.

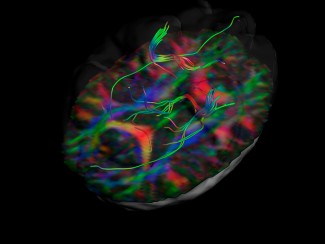

It is crucial to be able to track seizures through continuous EEG recordings, combined with video, when there is uncertainty around another potential diagnosis, or when surgical treatment is being considered.

Symptoms of epilepsy

In focal seizures, the most commonly seen symptoms are:

Uncontrolled muscle contractions in the upper or lower limbs. For example:

- Myoclonic seizures: brief and intense muscle contractions that can cause falls

- Clonic seizures: rhythmic, repeated shaking

- Tonic seizures: isolated muscle contractions

- Tonic seizures: stiffening of muscles, which can cause the patient to fall.

Visual, auditory, gustatory or olfactory hallucinations

Numbness in a limb with a ‘skin crawling’ or tingling sensation

Language problems

Heart rate or respiratory disorders (apnea), hypersalivation

Memory problems: illusions of déjà vu or déjà vécu, incongruous recollections of old memories.

Focal seizures may be accompanied by a loss of contact (or loss of consciousness) where the patient does not interact with people around them and becomes at risk of severe trauma. Sometimes, focal seizures can engulf the whole cortex: the patient loses consciousness, falls and convulses (secondary generalized or bilateralized seizure).

In seizures that are generalized from the outset, 3 types of symptoms can be identified:

- Absences’ during which the patient loses consciousness, does not fall, and remains immobile for an average of 5 seconds.

- Myoclonic seizures, particularly in the morning, when the patient has slept poorly

- ‘Tonic-clonic’ convulsive seizures that are generalized from the outset.

Epileptic seizures generally have a combination of these symptoms, with the most dramatic and well-known being the ‘tonic-clonic’ seizure. During this type of epileptic episode, there is a series of ‘tonic’ and then ’clonic’ motor signs and a loss of consciousness. These seizures are often accompanied by the patient biting their tongue, leaking urine, screaming, and hypersalivation. As the seizure abates, the patient becomes drowsy and slower.

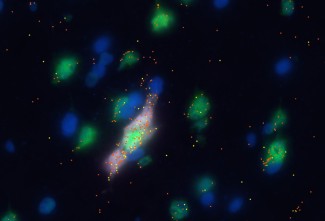

At Paris Brain Institute

An absence seizure is a frequent epileptic syndrome that accounts for 10 to 15% of childhood epilepsies. It presents as the repeated occurrence of seizures (up to 200 times per day) that interrupt all forms of conscious processes. Although it is known that, in children, these symptoms are caused by a defect in the cerebral cortex, we do not yet know how this brain region progressively acquires its ability to cause seizures. Professor Stéphane Charpier’s team has shown that, in this type of epilepsy, there is a cortical neuron focus causing these absence seizures, and that these spread via a deep brain structure, the thalamus, to all the cortical neurons.

A rare and tragic consequence (1 in 1,000 patients) of epilepsy is sudden and unexpected death (SUDEP), which can happen during a convulsive seizure. The mechanisms involved – respiratory, cardiac and cerebral – are not yet fully understood. A study by Stéphanie Baulac’s team at Paris Brain Institute focuses on cardiac functions in a cohort of patients at risk of SUDEP, who are carrying a mutation of the DEPDC5 gene. The cardiac origin could be ruled out. Seizure-induced apnea appears to be the trigger. Future research into brain activity in SUDEP looks set to shed light on the mechanisms that cause this tragic consequence of epilepsy.

Status epilepticus

Status epilepticus is defined as a seizure that lasts for more than several minutes.

- A generalized convulsive seizure usually stops on its own after 1 or 2 minutes. In exceptional cases, a seizure can last for more than 5 minutes: this is known as generalized status epilepticus. This is a medical emergency because the patient has stopped breathing and is at risk of cardio-respiratory arrest.

- Any other type of seizure can also evolve into status epilepticus: we can therefore talk about focal status epilepticus with, for example, motor activity in one arm when it lasts for more than 10 minutes. This type of status epilepticus is not life threatening but can lead to neurological aftereffects, caused by damage to neurons undergoing hyperstimulation.

The epilepsy and neurological resuscitation teams at Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital are experts in treating the most severe forms of status epilepticus, especially those that begin very suddenly and with no previous history of epilepsy. NORSE (new onset refractory status) can last for weeks, and requires anesthetic drugs as well as immunosuppressants, as it is often linked to pronounced inflammation in the brain.

Dr Aurélie Hanin, within Professor Vincent Navarro’s research team at Paris Brain Institute, has conducted many studies on the biomarkers of status epilepticus, showing that a daily blood test can accurately assess whether or not the status epilepticus is likely to recur (Hanin et al., European Journal of Neurology 2022). In collaboration with Dr Mario Chavez, within the same team, it was possible to identify prognostic factors for healing based on a combination of biological assays and clinical information, and by using artificial intelligence methods (machine learning) (Hanin et al., Journal of Neurology, 2022).