Although progressive paralysis of muscles is the main symptom of Charcot’s disease, it can progress in very different ways for each patient.

Symptoms, progression and life expectancy with Charcot’s disease

The symptoms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Charcot’s disease, typically include complete paralysis of the muscles in the arms, legs and throat, over time leading to an inability to walk, eat, talk and even breathe. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) begins in adulthood between the ages of 40 and 80, and will progress within 3 to 5 years to complete paralysis and death, usually due to paralysis of the patient’s respiratory muscles.

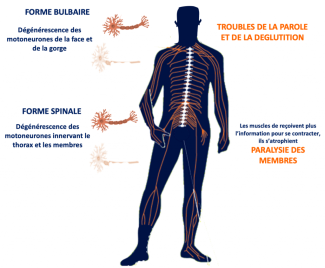

Depending on the location of the motor neurons affected at disease onset, the initial symptoms of Charcot’s disease will differ:

- In most cases, the disease begins with motor weakness in the upper or lower limbs. This is known as the spinal form of the disease. The affected limbs may atrophy and become flaccid when the peripheral motor neuron is most affected, or become stiff when the central motor neuron is most affected. Patients typically experience cramping and fasciculations (small, brief and involuntary muscle contractions without joint movement). Muscle weakness is localised at first, but then becomes worse and gradually spreads to other regions of the body.

- In around 30% of cases, Charcot’s disease begins with damage to the motor neurons in the brain stem (bulbar-onset ALS), and the first symptom is difficulty articulating words. Most often, this is soon combined with difficulties in swallowing, with silent aspirations. In this form of the disease, there is also excessive saliva in the mouth, as well as high emotional sensitivity.

- In rarer cases (around 10%), the disease may begin with damage to the musculature of the neck, causing ‘drooped head syndrome’ and difficulty remaining upright when walking, and/or shortness of breath.

- In most cases, the disease begins in one region of the body and spreads to others, so that patients with a spinal form of the disease may later develop bulbar-onset symptoms, or vice versa.

- All patients will experience impairments in their breathing muscles, causing respiratory failure in the later stages of the disease. It is this respiratory failure that will affect patients’ prognosis and eventually result in death.

At Paris Brain Institute

Decoding the role of immunity in Charcot’s disease

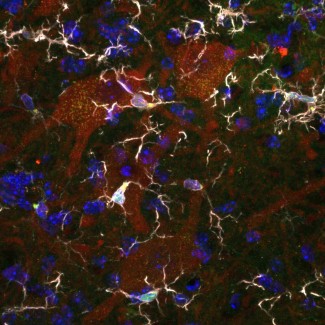

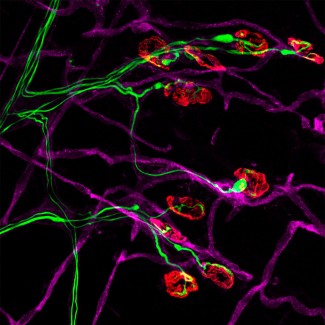

Séverine Boillée studies how immune cells (or inflammatory cells) influence motor neuron degeneration and disease progression. In ALS, there are more inflammatory cells around the motor neuron than in subjects who do not have the disease. These cells react to the degeneration of motor neurons and are involved in the progression of Charcot’s disease. In the brain and spinal cord, motor neurons interact with microglial cells, while in the peripheral nervous system they are in contact with macrophages. These two types of cells play a dual role: a positive role, by releasing agents beneficial for the survival of motor neurons, and a negative role, via toxic agents that will contribute to their destruction. The work by Séverine Boillée and Christian Lobsiger aims to better understand the role these cells play in the development and progression of Charcot’s disease, to identify new therapeutic approaches. The aim is to specifically analyze the different agents released by these cells and to identify which to act on to slow the progression of the disease.

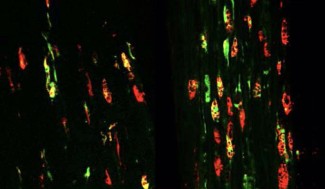

Early brain impairments in individuals at risk of developing ALS

A study led by Paris Public Hospital Network (AP-HP) and conducted at Paris Brain Institute at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital by Isabelle Le Ber within Alexandra Durr and Giovanni Stevanin’s team, and Olivier Colliot co-team leader with Stanley Durrleman has found, for the first time, that asymptomatic individuals at risk of developing frontotemporal degeneration (FTD) or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) because they carry the C9ORF72 gene have very early cognitive, anatomical and structural impairments, before the age of 40. Identifying biomarkers at very early stages is a first step towards developing the tools needed to evaluate new treatments. Developing early-stage therapeutics, ideally before the onset of symptoms, requires the development of tools that can tell us when to begin treatments, and to measure their efficacy.