Frontotemporal degeneration usually manifests through concurrent or successive behavioral and language problems. Progression toward loss of language and independence is variable in terms of time frame.

Symptoms of Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD)

The disease progresses gradually. The symptoms of FTD are highly variable from patient to patient, in their manifestations as well as in their order of onset and progression. FTD is initially suspected based on reports from family members who notice changes in an individual’s behavior, personality, or language skills. There are several forms of the disease, beginning with behavioral problems (behavioral covariates of FTD) or language problems (progressive aphasia).

In the early stages of behavioral FTD, behavioral problems are subtle and can resemble depression or other cognitive disorders (such as Alzheimer’s disease). The first symptoms are often apathy, loss of motivation, emotional indifference, or loss of interest in others.

Other symptoms may be present at the onset of the disease or as it progresses. Behavioral problems include verbal or behavioral disinhibition and an inability to respect social norms (inappropriate comments, failure to follow social rules in public places, for example). Patients may exhibit repetitive gestures, experience fixations, or develop compulsive behaviors. A lack of patience (impulsiveness) and excessive irritability are sometimes observed.

Changes in eating behavior such as gluttony, bulimia, and rushing to eat are also common.

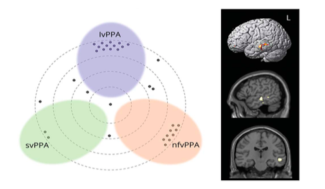

Progressive aphasias are characterized by language problems in two forms (non-fluent progressive aphasia and semantic dementia). Aphasia is a loss of language characterized by difficulties in finding words, constructing sentences correctly, or understanding language, which progresses to a total loss of language and an inability to communicate.

As in the behavioral form of the disease, cognitive impairments are associated with the onset or progression of language problems, such as executive difficulties.

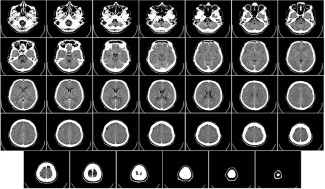

Additional tests can confirm the diagnosis of FTD. Neuropsychological tests make it possible to assess cognitive functions, particularly reasoning, judgment, attention, and memory. They may be supplemented by a language assessment (speech therapy evaluation). Brain imaging tests, such as MRI or PET scans, reveal atrophy of the frontal and temporal regions. Biological tests, a lumbar puncture, or an electroencephalogram can rule out other conditions with similar symptoms.

For familial forms, which account for approximately 30% of cases, a consultation and genetic testing may be offered to identify the mutation responsible for the disease.

At Paris Brain Institute

One of the important objectives of the research conducted at Paris Brain Institute and IM2A is to improve patient diagnosis in order to detect the disease earlier and limit diagnostic uncertainty. FTD can be confused with several other conditions depending on the stage, such as mood disorders (depression, bipolar disorder) or anxiety disorders (obsessive-compulsive disorder), or even Alzheimer’s disease.

Isabelle Le Ber and Paola Caroppo, in collaboration with neuroimaging teams and the Clinical Investigation Center at Paris Brain Institute, have used cutting-edge brain imaging techniques to identify a very limited region of the brain involved in language comprehension, the ability to interact with others, and facial emotion recognition (impaired in patients with FTD), which could be the site of the first brain lesions in a genetic form of FTD. This major discovery has made it possible to locate the site of biological mechanisms, in particular neuronal death, even before the onset of clinical symptoms.

Patients with frontotemporal dementia (FTD) are unable to categorize objects. By studying patients with frontal cortex damage, researchers from the FrontLAB: Frontal Functions and Pathology team led by Dr Richard Lévy have shown that categorization within the brain involves different functions, namely the ability to gather information and the ability to abstract. These two mechanisms depend on specific regions within the frontal lobes. This study paves the way for the use of concept formation tests as a diagnostic tool for DFT.

A study by Marc Teichmann and Carole Azuar from Professor Richard Lévy’s team at Paris Brain Institute and Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital (APHP) highlights a particularly marked impairment of moral emotions, such as admiration, shame, and pity, in patients with frontotemporal degeneration. The results provide new possibilities for early, sensitive, and specific diagnosis of patients with DFT.

https://parisbraininstitute.org/news/moral-emotions-diagnotic-tool-frontotemporal-dementia

Data sheet updated with the assistance of Isabelle Le Ber, neurologist, researcher in the FrontLAB team at Paris Brain Institute and coordinator of the reference center for rare and early dementias.