Could exploring the relationships between different brain networks help us understand frontotemporal dementia (FTD)? This neurodegenerative disease, which progresses at varying rates, is often diagnosed late—when clinical signs are already severe. At Paris Brain Institute, Arabella Bouzigues, Lara Migliaccio, and their team show that the functional organization of patients' brains might one day provide helpful imaging markers to detect early changes and track the disease's progression. Their findings are published in Molecular Psychiatry.

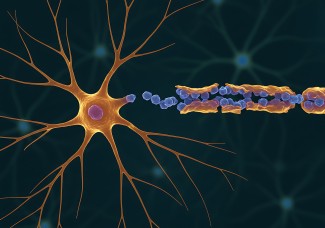

Neurodegenerative dementias are a group of diseases characterized by the progressive death of neurons and a significant cognitive decline. These include frontotemporal dementia (FTD), which affects around 1 to 10 people per 100,000. It is marked by the degeneration of the frontal and, sometimes, temporal lobes, leading to personality changes, behavioural issues, and language impairment.

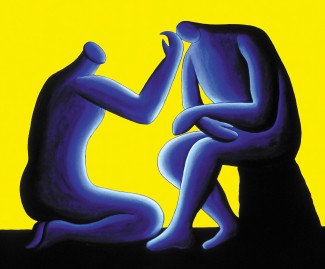

Depending on the form of the disease, patients may appear apathetic, impulsive, indifferent to others’ emotions, or struggle to understand and express language. Some may also behave inappropriately in social settings. Families and caregivers often feel helpless in the face of these symptoms, which they don’t immediately associate with a neurodegenerative condition—especially since the disease often affects young, active individuals.

Since patients are often unaware of their condition and don’t seek medical attention, FTD is difficult to detect. There is a critical need to understand better the degenerative processes behind the vast array of cognitive and behavioural symptoms, enabling early diagnosis and avoiding confusion with psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, bipolar disorder, OCD) or other dementias.

Investigating The Organization of Brain Networks

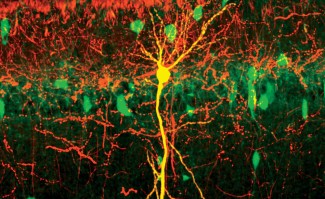

“The emergence of cognitive and behavioural functions—such as decision-making, language, or responding to sensory stimuli—doesn’t arise solely from the activation of specific brain networks, but from their interplay,” Arabella Bouzigues, a doctoral researcher, explains. “These interactions are disrupted in neurogenerative diseases in general and FTD in particular. We wanted to understand how.”

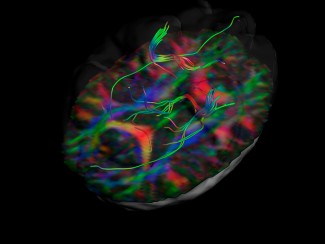

At Paris Brain Institute, Arabella Bouzigues, Lara Migliaccio and their colleagues investigated the organization of these networks in 77 patients and 52 healthy individuals using functional MRI (fMRI). This technique allowed them to study “gradients”—i.e. spatial transitions between different brain networks—and their hierarchy within brain function.

The researchers found that, in healthy individuals, a first gradient clearly separates the sensorimotor network—which manages movement optimization and sensory interpretation—from the so-called “default mode network”, which comes into play when an individual is at rest. A second gradient distinguishes the visual network from the “salience network”, which prioritizes information for action.

Some patients with frontotemporal dementia struggle to grasp the meaning of what is said to them and to respond meaningfully by engaging in reasoning. They often overlook the emotional content of others' words, which can be distressing for those around them and further contribute to their social isolation. Credit: Michele Angelo Petrone, Wellcome Collection.

In contrast, FTD patients showed significant disruptions in this organization, with variations depending on the disease subtype. In the "language variants" of FTD, disruptions were focal, primarily affecting the limbic and sensorimotor gradients. In the “behavioural variant”, however, the entire gradient hierarchy was compromised. Interestingly, the visual network appeared to compensate for cognitive and behavioural deficits across all forms of the disease.

New Biomarkers?

“One of our most surprising findings in this study is that the altered networks don’t overlap with areas of brain degeneration,” Bouzigues adds. “In other words, the severity of symptoms is determined by the inability of different networks to collaborate—and not just by the loss of neurons, causing brain atrophy.”

These functional markers of frontotemporal dementia could contribute to disease detection, tracking disease progression, and even identifying new therapeutic targets.

“This is an exciting prospect, especially as therapeutic advancements are finally being made in various neurodegenerative diseases: gene therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, newly approved anti-amyloid treatments in Europe for Alzheimer’s disease... Early diagnosis has never been more important,” Migliaccio concludes. “Understanding brain organization goes beyond theoretical knowledge—it can directly inform the development of new treatments and provide markers to evaluate their effectiveness.”

Funding

This study was funded by the Recherche Alzheimer Foundation and the Vaincre Alzheimer Foundation.

Reference

Bouzigues, A., et al. Disruption of macroscale functional network organisation in patients with frontotemporal dementia. Molecular Psychiatry, November 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41380-024-02847-4.

Sources

Bouzigues, A., et al. Disruption of macroscale functional network organisation in patients with frontotemporal dementia. Molecular Psychiatry, Novembre 2024. DOI : 10.1038/s41380-024-02847-4.

The goal of the Frontlab team is to understand better the role and organization of the prefrontal cortex in the control, activation, and inhibition of goal-directed behaviours.

Read more