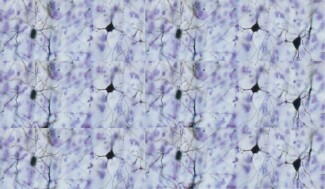

Parkinson’s disease typically involves the death of a certain type of neuron – dopamine-secreting neurons known as ‘dopaminergics’, which tend to be located in a very small region of the brain called the dark matter or ‘substantia nigra’.

Biological mechanisms of Parkinson's disease

Neurons, cells well known in the brain, communicate with each other through synaptic transmission; the synapse being the space between two neurons. While information travels from one end of a neuron to the other through an electrical current called action potential (or nerve impulses), synaptic transmission requires intervention by proteins.

These molecules are secreted by neurons upstream of the synapse and bind to specific receptors carried by the next neuron, called neurotransmitters.

Dopaminergic neurons use just one neurotransmitter to communicate with each other and with other types of neurons: dopamine.

The dark matter located in the brain stem is very small, the size of a lentil, and is made up of around 400,000 dopaminergic neurons. This area of the brain and its neurons form a network with other brain areas such as the striatum, a region that plays a major role in movement control, but also in cognitive and behavioral functions.

In Parkinson’s disease, for reasons that are not yet clear, dopaminergic neurons gradually die off, causing a slow decline in dopamine levels in the dark matter, but also in the regions connected to this area.

The first symptoms of Parkinson’s disease are believed to emerge when 50% of dopaminergic neurons have been impaired.

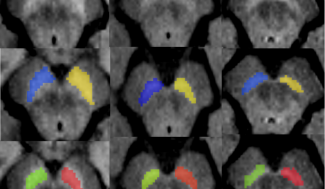

In the surviving neurons, clusters of a specific α-synuclein protein called Lewy bodies are observed. These aggregates, found in the cell body (close to the nucleus) and in the neuron extensions (dendrites and axons), are responsible for the death of neurons and therefore for the gradual depletion of dopamine.

In addition to α-synuclein deposits in the neurons, the protein is found in other cell types and in the space between two neurons (the synapse). This explains the spread of the disease and neuronal degeneration.

Deposits of the protein are therefore seen outside the dark matter, particularly in the olfactory bulb, the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, the coeruleus/subcoeruleus complex and the spinal cord in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

The same thing happens in the peripheral nervous system, particularly in the salivary glands and certain organs such as the heart and digestive tract.

The aggregates of α-synuclein outside the dark matter explain why the ‘non-motor’ symptoms observed in patients are so heterogeneous. These symptoms are currently difficult to treat, but the recent discovery of the key role played by α-synuclein opens up new pathways for therapeutic approaches.

At Paris Brain Institute

The teams of Olga Corti and Professor Jean-Christophe Corvol, and of Stéphane Hunot and Etienne Hirsh are conducting research to better understand the molecular and cellular mechanisms behind Parkinson’s disease.

Olga Corti and her team are working to identify the physiological consequences of mutations identified in familial Parkinson’s disease cases, as the mechanisms are the same in all patients. This team is especially interested in mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochrondria are organelles whose role is to supply energy to the cell and ensure it survives. Mitochondrial dysfunction seems to play an important role in neuron degeneration. In May 2019, this team identified a combination of proteins involved in the pathological mechanism of Parkinson’s disease, and this molecular combination can be a biomarker or therapeutic target.

Etienne Hirsh and Stéphane Hunot’s team is particularly focused on the neuroinflammation that accompanies the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease and, in particular, the role