Assessing a number of elements, whether individuals in a group, twigs in a nest, or fruit on a branch, is an essential skill in many animals. But the neural circuits on which it is based are still poorly understood. To remedy this lack of knowledge, Mercedes Bengochea and her colleagues at Paris Brain Institute have developed a model of numerical cognition in fruit flies. Their results show that these insects can discriminate between sets containing different numbers of objects and spontaneously show a preference for larger numbers. This numerical judgment requires the activation of specific neurons, the LC11s. Located in the optic lobe, they also intervene in a social context, enabling the fly to adapt its behavior in response to a threat. The ability to “count” friends and foes may have played a role in the evolution of fruit flies, explain the researchers in a new study published in Cell Reports.

In the animal world, you don't need to learn a numeral system – such as the ten-digit Indo-Arabic system we commonly use – to be able to count. Animals constantly use numerical information from their environment to make decisions. Estimating the number of conspecifics in a competing group before engaging in conflict, the amount of food available in a difficult-to-reach location, or the number of potential sexual partners in a new territory is essential for survival and reproduction. This skill can reach an astonishing level of refinement; for example, certain species of ants orient themselves in the desert by estimating the number of steps required to reach a target.

Numerical sensitivity, i.e., the ability to perceive information related to quantities, exists in many vertebrates and invertebrates. It has been documented in primates, birds, amphibians, fish, and bees. You don't need to enumerate numbers to distinguish between one, two, several and many! However, we didn't know which neuronal circuits were involved in this skill.

To investigate this question, researchers must record the brain activity of an animal during a numerical task, then activate or deactivate specific neural cells to determine which areas of the brain are involved. These operations are difficult to carry out on vertebrates, but the right tools already exist with fruit flies. “Drosophila melanogaster is a model of choice for studying cognition. These insects adjust their behavior in the face of a threat according to the number of fellow flies who could help, adds the researcher. In the event of imminent danger, the smaller the size of its group, the more likely they are to freeze to stay safe.”.

A lot is never too much

To determine whether fruit flies can accurately evaluate numbers and assign values to perceived quantities, Mercedes Bengochea and her colleagues used an experimental setting that has already proven its relevance. They placed the flies in arenas called “Buridan arenas”, where they were exposed to visual stimuli: in that case, two sets of objects. The researchers then determined which stimulus the insects preferred by measuring the time they spent inspecting either set.

Their results indicate that fruit flies stayed longer near the set containing three objects than the set that had only one – regardless of the size of the objects or the total volume occupied by the set. This taste for larger quantities was preserved when the insects had to choose between groups of 2 or 4 objects and 2 or 3 objects. “The flies, however, were unable to distinguish between sets of respectively 3 and 4 objects, explains Mercedes Bengochea. It seems that the ratio between these two numbers is not sufficient for them to perceive a difference. On the other hand, they can very easily compare a group of 4 and a group of 8 objects – a ratio of simple to double”. Fruit flies are, therefore, not limited to counting to 3: the ratio between the quantities evaluated must be clear enough to be perceived.

Assessing the ratio between two quantities is a simple visual task common in animals. It is also handy for humans, as it allows us to gauge at a glance the size of a group that contains too many elements to be counted one by one – a crowd at a concert, for example.

Counting without absolute values

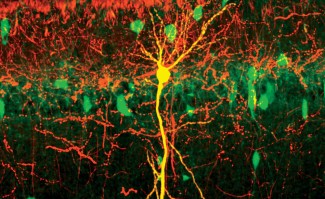

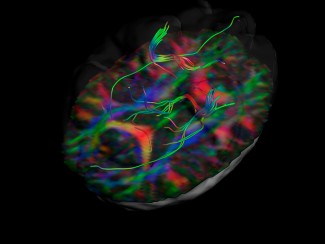

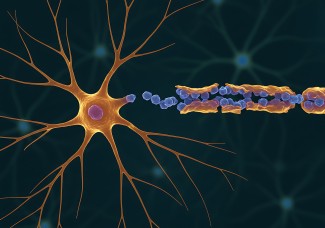

Which neural circuits are involved in this system of numerical discrimination in Drosophila remains to be determined. To do this, the researchers successively “switched off” different areas of the insects' brains, preventing the transmission of nerve signals at synapses. After several tests, they observed that the activity of a column of neurons located in the optic lobe, LC11 neurons (for lobular columnar neurons 11), was necessary for flies to distinguish different sets of objects.

“In a second experiment, we taught the insects to go against their natural inclination for large numbers, using a simple conditioning method: an appetizing dose of sugar was placed next to the smallest sets of objects, adds the researcher. Momentarily, thanks to the lure of the food, we made them prefer the small numbers. But once the LC11s had been inactivated, the insects no longer showed any preference... for either large or small quantities. This confirms that these neurons are essential for comparing quantities, regardless of the value fruit flies assign to them.”

LC11s are also involved in the social behavior of fruit flies: they are activated when insects must adapt their defense strategy according to the number of congeners flying nearby.

We believe that the ability to assess quantities has been decisive in the evolution of invertebrates. The cognitive solutions insects use to ‘count’ are very simple. Several studies have shown that, in a computational model, a few artificial neurons are enough to perform a numerical task.

Flies will never help us do our accounting. However, like other insects, we are often tempted to underestimate their cognitive abilities and the subtlety of their social behavior. It's a mistake made even more regrettable because, without them, our understanding of the human brain would remain terribly limited.

Funding

This work was supported by the Investissements d’Avenir program, Paris Brain Institute core funding, the Allen Distinguished Investigator award, the Roger De Spoelberch Prize, an NIH Brain Initiative grant, ANR grant QuantSocInd, and The Big Brain Theory Program from Paris Brain Institute.

Sources

Bengochea M. et al. Numerical discrimination in Drosophilia melanogaster. Cell reports (14 juillet 2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112772

other sources

Rooke R. et al. Drosophila melanogaster behavior changes in different social environments based on group size and density. Communications Biology (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-1024-z

Vasas, V. et al. Insect-Inspired Sequential Inspection Strategy Enables an Artificial Network of Four Neurons to Estimate Numerosity. iScience(2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2018.12.009