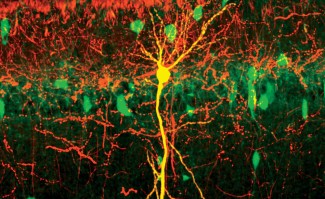

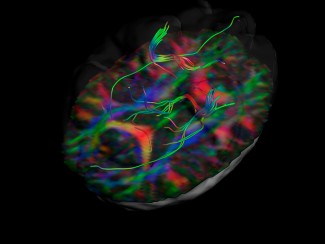

Whatever the alphabet we use or the culture in which we are raised, it’s always the same small region of the visual cortex in the left hemisphere that allows us to identify the letters we see. Why, then, in the vast regions of the visual cortex that we use to recognize the things around us, is it this precise zone that is specialized in reading, whereas its close neighbors are specialized in the recognition of faces or places? To answer this question, researchers in the Brain and Spine Institute (Pr. Laurent COHEN, PICNIC LAB) used “diffusion” magnetic resonance imaging to trace the white matter fibers that permit the different regions of the brain to communicate with each other. With this technique, they showed that the region of letter recognition has privileged relations with regions that carry out the understanding and production of speech, whereas the region dedicated to facial recognition is more connected with systems implicated in emotions and social relations. The anatomy of the brain communication pathways is thus decisive for the way a cultural invention such as writing finds its place in our brain.

At birth, nothing distinguishes the brain of a contemporary infant from an infant born ten thousand years ago, well before the invention of writing. Our brain is thus not particularly predisposed to reading. However, when a child learns to read today, he does it with exactly the same brain regions, whatever the language, the alphabet, the culture in which he is raised. In particular, it is always the same small region of the visual cortex in the left hemisphere that learns to recognize the letters we see. Why then, in the vast regions of the visual cortex that we use to recognize what is around us, is this precise zone specialized in reading, whereas its close neighbors are specialized in the recognition of faces or places?

The researchers of the PICNIC Lab at the Institut du Cerveau - ICM showed in an article which has been just published (Bouhali et al., Journal of Neuroscience) that it is because this zone has particularly strong connections with the regions of language, those that permit, once the letters of a word are recognized, to understand and pronounce the word.

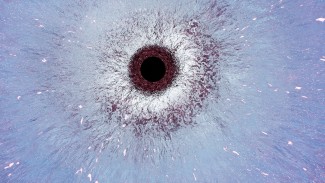

To do this, they used diffusion magnetic resonance imaging to visualize the white matter fibers that allow the different parts of the brain to communicate with each other. In 75 subjects, they started from either the region of letter recognition or the contiguous region involved in facial recognition. They then followed the white matter tracts to identify the cortical regions to which they are connected. Comparison of the territories connected to the two initial seed regions showed that letter recognition is preferentially linked to language areas, whereas the region of facial recognition is more connected to systems implicated in the emotions and social relations.

The anatomy of the brain’s communication pathways is thus decisive in determining brain function, and notably the way in which a cultural invention like writing is taken in charge by our brain.