A research team from Inserm, CNRS, Sorbonne University and AP-HP at the Paris Brain Institute in Paris just deciphered how our brain behaves when we procrastinate. The study, conducted in humans, combines functional imaging and behavioral testing. It led to identify a region of the brain where the decision to procrastinate is made: the anterior cingular cortex. The team also developed an algorithm to predict participants' tendency to procrastinate. This work is published in Nature Communications.

Procrastination, or the tendency to postpone tasks that we are supposed to do, is an experience - often uncomfortable and even guilty - that many of us have already lived. Then why, and in which conditions, does our brain push us to procrastinate? To answer this question, a team led by Mathias Pessiglione, Inserm researcher, and Raphaël Le Bouc, neurologist at the AP-HP, from the Paris Brain Institute (Inserm/CNRS/Sorbonne University/AP-HP) conducted a study with 51 participants.

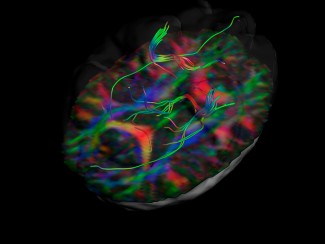

In order to decipher procrastination behavior, these individuals participated in a number of tests during which their brain activity was recorded by MRI. Each participant was first asked to subjectively assign a value to rewards (cakes, flowers...) and efforts (memorizing a number, doing push-ups...). They were then asked to indicate their preferences between getting a small reward quickly or a large reward later, as well as between a small effort to be made right away or a larger effort to be made later.

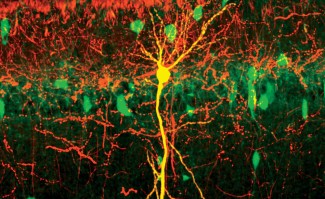

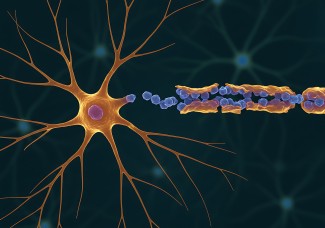

The imaging data revealed activation during decision making in a brain region called the anterior cingulate cortex. This region is responsible for performing a cost-benefit calculation by integrating the costs (efforts) and benefits (rewards) associated with each option.

The tendency to procrastinate was then measured by two types of tests. In the first, participants were asked to decide whether to produce an effort on the same day to obtain the associated reward immediately, or to produce an effort on the following day and wait until then to obtain the reward. In the second, upon returning home, participants had to fill out several rather tedious forms and return them within a month to be compensated for their participation in the study.

The MRI data and the tests scores feed a mathematical model of decision making, called "neuro-computational", developed by the researchers.

Our model takes into account the costs and benefits of a decision, but also integrates the deadlines when they occur. For example, for a task such as washing dishes, the costs are linked to the long and boring aspect of the chore and the benefits to the fact that the kitchen is clean at the end of the task. Washing the dishes is very tedious in the moment; considering doing it the next day is a little less so. Similarly, being paid immediately after a job is motivating, but knowing that you will be paid a month later is much less so. It is said that these variables, the cost of effort as well as the value of rewards, diminish with time, as they move further into the future

Using information about the activity of their anterior cingular cortex and data collected during behavioral testing, the researchers established a motivational profile for each of the participants. This profile described their attraction to rewards, their aversion to effort, and their tendency to devalue benefits and costs with time. Considering those profiles researchers were able to estimate the tendency to procrastinate for each of the participants. Thanks to their model they were able to predict how long it would take for each participant to return the completed form.

This research could help to develop individual strategies to stop putting off chores that are within our reach. They could also help avoid the pernicious effects of procrastination in fields as varied as education, economics and health.

Sources

A neuro-computational account of procrastination behaviour

Le Bouc Raphaël 1,2 & Pessiglione Mathias 1

1Motivation, Brain and Behavior (MBB) Lab, Paris Brain Institute (ICM), Sorbonne University, Inserm, CNRS, Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital, Paris, France.

2Department of Neurology, Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital, Sorbonne University, Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris (APHP), Paris, France.

Nature Communications, septembre 2022