No treatment currently exists that can stop the silent progression of multiple sclerosis, and many promising drugs have proved ineffective in clinical trials. To reduce this failure rate and better predict the potential of candidate molecules, researchers at Paris Brain Institute, coordinated by Bernard Zalc, have developed a new model of the disease described in Brain. It makes it possible to correlate the degeneration or regeneration of myelin with the evolution of cognitive and motor abilities. On the horizon: better targeting of molecules likely to promote remyelination and halt disease development.

In multiple sclerosis (MS), the immune system mistakenly attacks the brain and spinal cord, causing the complete loss of myelin.

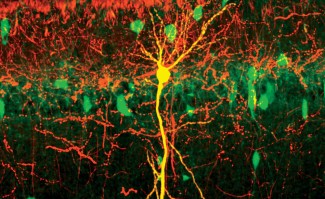

Synthesized by specialized cells, oligodendrocytes, myelin protects nerve fibers, guarantees the good conduction of nerve impulses, and provides nutrients to the axons. This protective sheath envelops nerve fibers and is essential for their proper functioning. Its disappearance, called demyelination, causes sensory and motor symptoms: weakness of the lower or upper limbs, loss of balance, sensitivity, and vision disorders.

Over the past 30 years, considerable therapeutic advances have been made in controlling the inflammatory component of multiple sclerosis, thereby reducing the damage caused by the immune system during relapses of the disease. Despite this progress, there is still a progression of disability in patients, even though they are treated with effective immunotherapies. The reason? Neurodegeneration. Essentially independent of inflammation... it justifies the need for restorative treatments.

However, repairing myelin sheath lesions – or remyelination – is a real challenge. Clinical failures have multiplied over the years.

Why do candidate molecules systematically disappoint us when tested in humans? One possible explanation: at the preclinical stage, they are evaluated on their ability to generate new myelin-producing cells. This criterion, based on tissue observation, is not sufficient. For the drug to be effective, it must also improve the symptoms of the disease or even completely restore sensory and motor capacities, the researcher explains. But at present, it is difficult to make the connection between a given demyelinating lesion and a specific sensorimotor deficit.

A bridge between lesions and behavior

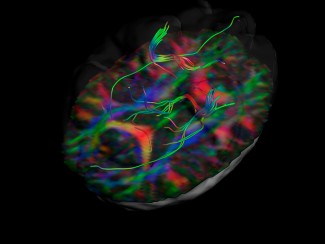

To fill this gap in understanding, researchers from Catherine Lubetzki and Bruno Stankoff's team at Paris Brain Institute have imagined a new tool. They used genetically modified Xenopus tadpoles, an amphibian with a perfectly transparent body at this stage of development. This feature makes it easy to count the number of myelin-producing oligodendrocytes within the optic nerve, then correlate this indicator with the motor and behavioral abilities of the animal.

Because changes in the number of oligodendrocytes indicate a process of demyelination or remyelination, the team developed a process to induce these events on demand: the researchers introduced a substance called metronidazole into the tadpole aquarium, which, under the conditions in which it was used, caused the loss of oligodendrocytes in the animals’ optic nerve. This loss was correlated with impaired visual abilities – assessed by a virtual target avoidance test.

After exposure to metronidazole, researchers observed spontaneous myelin repair, as measured by an increase in the number of oligodendrocytes and improvement in visual test results. They then showed that this phenomenon could be accelerated by presenting tadpoles with molecules that promote remyelination.

Our results show that variation in motor and sensory performance is perfectly correlated with the level of demyelination and tissue remyelination. This model is thus ideal for testing the remyelination potential of new drugs before launching long and costly clinical trials

There is an urgent need to find molecules capable of acting on demyelination, which, in its chronic form, leads to irreversible axon damage responsible for neuronal death. Disability then progresses inexorably.

This new tool, which allows in vivo monitoring, has the potential to advance our knowledge of the link between visual disorders – one of the most common symptoms of multiple sclerosis – and associated demyelination lesions, the researcher concludes. This is a real launchpad for future therapeutic success.

Funding:

This study was carried out with funding from the Investissements d'avenir program, the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, the ENDpoiNTs project, the BRECOMY grant from DFG and ANR, the MADONA grant from ANSES and the IONESCO grant from NeurATRIS.

Sources

Henriet. et al. Monitoring recovery after CNS demyelination, a novel tool to de-risk pro-remyelinating strategies. Brain (2023) Mar 30:awad051. doi.org/10.1093/brain/awad051