Restlessness in sleep is common, however it may be a symptom of two illnesses that seem to be complete opposites: sleepwalking and behavioral disorders in REM sleep. The first affects a younger population and takes place during deep sleep, whereas the second mainly affects older patients and is often linked to neurodegenerative illness. However, a recent study carried out by Institut du Cerveau - ICM and APHP doctors and researchers found that certain characteristics of sleepwalking and behavioral disorders in REM sleep converge. These results could have an impact on diagnosis and patient care.

Sleepwalking and night terrors are considered abnormal behavior in deep sleep. Patients with low levels of consciousness are able to open their eyes, sit, scream, run, walk, hold onto objects, speak, or answer questions, for example – but often in an inappropriate fashion. Sleepwalking and night terrors mostly affect children and young adults, with high familial predisposition.

Conversely, behavioral disorders in REM sleep mainly affect individuals over 50. They are often associated with Parkinson’s disease or various types of dementia, as a precursor or associated disorder. Many studies have highlighted the link between Parkinson’s disease and sleep. Behavioral disorders are characterized by gesticulation, sudden arm and leg movement, laughs, speaking and screams. This type of behavior usually takes place in the patient’s bed and is not associated with walking. Patients describe the behavior as an attempt to act during dreams or nightmares.

These two disorders shouldn’t have any shared characteristics. However, previous studies found that in rare cases, some elderly patients had both behavioral disorders in REM sleep and experienced sleepwalking. Could this mean that the two illnesses share common characteristics?

To gain a deeper understanding of the question, doctors and researchers from the Institut du Cerveau - ICM and the sleep pathologies unit at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital examined 62 patients with sleepwalking or night terror disorders, 64 patients with behavioral disorders in REM sleep, 66 healthy elderly patients and 59 healthy young patients.

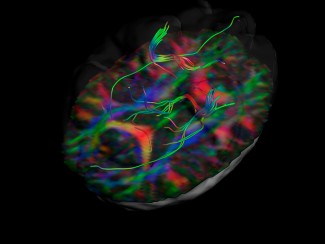

Participants answered a series of questions aiming at analyzing mental content and dreams during pathological episodes as well as their behavior, and took a video-polysomnography test in that records various physiological datasets including an encephalogram, heartrate, and muscular activity during sleep along with video recording.

Results show that typical characteristics of behavioral disorders in REM sleep such as intense dreams or nightmares and a feeling of physically “experiencing” them through gesticulation are often seen in sleepwalking patients. This observation has an impact on the specificity of questionnaires used in general population epidemiology to detect behavioral disorder in REM sleep, with possible false positives.

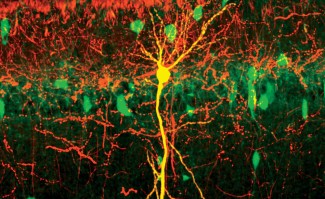

In addition to abnormal behavior in deep slow-wave sleep, patients with sleepwalking disorders or night terrors display muscle tremors and excessive jolts in REM sleep without exhibiting abnormal behavior in REM sleep. The origin of these tremors has yet to be found. They may be linked to greater REM sleep dreaming in sleepwalkers (explaining an increase in short tremors) or a lack of motor inhibition during both deep and REM sleep.

While the networks involved in sleepwalking have yet to be detailed (those at play in behavioral disorders have been clearly identified with damage to the locus subcoeruleus, that usually locks movement down in REM sleep), these results highlight that an individual complaining of intense nightmares or dream activity is not necessarily affected by behavioral disorders in REM sleep nor are they at risk for Parkinson’s disease. They may simply be affected by night terrors in deep slow-wave sleep. This makes it all the more important to record sleep activity and behavior of individuals that scream, are agitated, and gesticulate during sleep. Risk associated with self-harm or harming others may justify recommending a light course of treatment to reinstate true muscular relaxation during sleep.

Sources

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28513054/

Haridi M, Weyn Banningh S, Clé M, Leu-Semenescu S, Vidailhet M, Arnulf I. J Sleep Res. 2017 May 17