Spinocerebellar ataxias are a very heterogeneous group of inherited diseases associated with degeneration of the cerebellum – a region at the back of the skull that plays an essential role in motor control. Patients have gait and balance disorders that gradually worsen with time... but this is the only thing they have in common: spinocerebellar ataxias differ in their genetic origin, clinical manifestations, and evolution. To better understand this diversity and offer a personalized approach for each patient or family, the team led by Alexandra Durr (Sorbonne University, AP-HP) at Paris Brain Institute initiated a vast international collaboration, which made it possible to carry out the genetic study of 756 individuals. The findings are published in The American Journal of Human Genetics.

The major challenge with spinocerebellar ataxias (or SCA) is interpreting the extreme genetic variability observed in those who are affected. How can we establish the link between genetic characteristics, pathophysiological mechanisms, and specific symptoms when patients are so different from one another? What effect does this lack of knowledge have on patient care?

To interpret genetic data, it is essential that geneticists talk to clinicians. ACS affects 1 to 5 individuals per 100,000 people worldwide. Among these cases, there are even rarer forms of the disease, that are quite difficult to care for: we know very little about them. Our team, therefore, wanted to systematically describe all the variants already identified so that in the future, no patient is left on the sidelines.

Identifying rare forms

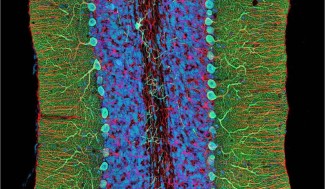

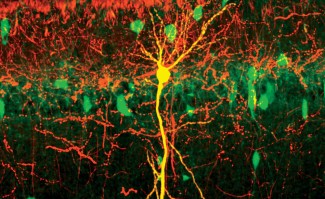

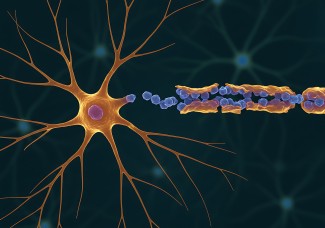

The most common spinocerebellar ataxias are called triplet diseases. Accounting for almost 60% of cases, they are caused by a genetic mutation based on the expansion of a trinucleotide repeat. This error causes the synthesis of polyglutamine proteins –toxic to specific populations of neurons in the cerebellum, spinal cord, or even the cerebral cortex and peripheral nervous system.

The remaining 40% of ataxias are due to other genetic abnormalities and are based on different pathophysiological mechanisms. Patients risk being lumped together with the best-known ataxias... or never receiving the correct diagnosis

There is an urgent need to reduce our lack of knowledge about other ACS. To this end, we combined clinical and genetic information from people who carried a pathogenic variant of the genes associated with spinocerebellar ataxias. To obtain robust results, all available data had to be aggregated! We called for fellow 'ataxiologists' around the world, and fortunately, they answered

This international collaboration allowed the researchers to gather 756 patients and compare the age of onset, course, and symptoms of the disease. Their results show that many stereotypes attached to spinocerebellar ataxias turn out to be inaccurate in these rare forms. It also emerged that the diversity of disease manifestations had been greatly underestimated so far.

Indeed, while the progression of the disease was relatively slow in all patients, it sometimes began in childhood.

For the same genetic mutation, ataxia occurs at birth in some and is associated with intellectual disability... while in others, it develops over 60 years old, Durr adds. These two cases have been observed in the same family

A limited predictive potential

Another surprise was that many of the patients were very young, with clinical features similar to those usually found in neurodevelopmental diseases. This contrasts with the best-known triplets ACS which generally manifests in adulthood, between 30 and 50.

Thanks to this study, our understanding of ataxias is being refined, enthuses the researcher. We can't establish correlations between molecular alterations and clinical signs yet, but we've taken a big step towards a better description, which is essential for genetic counseling.

It is likely that spinocerebellar ataxias are less rare than previously thought and that we underestimated the frequency of atypical presentations. Hence the interest in “sequencing of the coding parts of the genome (exome) or of the whole genome. This approach must become standard practice if we are to improve the diagnosis of ataxias", Alexandra Durr concludes.

Sources

Cunha et al., Extreme phenotypic heterogeneity in non-expansion spinocerebellar ataxias, The American Journal of Human Genetics, 2023. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2023.05.009