What if we could resist compulsions? These irrational behaviours, particularly common in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), are hard to suppress. At Paris Brain Institute, Éric Burguière's team shows that we can anticipate them and block them before they occur. These promising results, obtained in mice, could help us understand the biological mechanisms underlying compulsions. They are published in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

Touching repeatedly a particular object, biting your nails, washing your hands every ten minutes... these irrepressible rituals sometimes punctuate our lives, especially during periods of high anxiety. When they become invasive to the point of interfering with daily activities, they can become pathological: this is what we call compulsions—which are characteristic of several mental illnesses, including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Affected patients know that these behaviours are the product of their mental activity… but it does not always help them regain control. The compulsion sometimes imposes itself so violently that it disrupts professional activity and social life—to the point that patients isolate themselves to accommodate the symptoms.

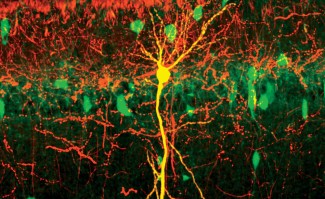

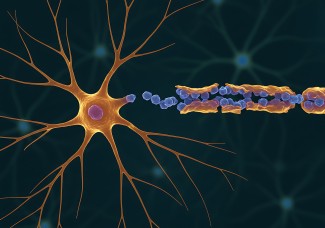

Recent research has shown that compulsive episodes are associated with dysfunction of brain circuits located in the orbitofrontal cortex—a region involved in decision-making—and in the striatum, beneath the cortex. However, the underlying neuronal anomalies remained to be identified.

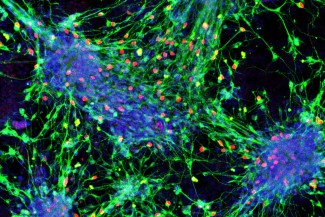

We had a suspect in mind: inhibitory interneurons, a type of nerve cells found in the striatum. Therefore, our team investigated to better understand the role of these cells in regulating behaviour.

Striatal interneurons under fire

First, Lizbeth Mondragón-González and Christiane Schreiweis, in Éric Burguière's team, selected genetically modified mice that are usually used to study OCD because they display a compulsive behaviour which is easy to observe and measure: they groom themselves excessively to the point of causing significant hair loss and skin irritation.

The researchers then used an optogenetics technique, which makes it possible to activate or inhibit neurons selectively using light rays to correct faulty neural circuits.

Their results are unequivocal: thanks to the continuous stimulation of the inhibitory interneurons in the striatum, the grooming of the mice became perfectly normal.

This confirms the involvement of inhibitory neurons in the compulsions of these animals. However, we did not want to stop there! Our goal is to understand when and how to intervene to stop the symptoms.

Nipping compulsion in the bud

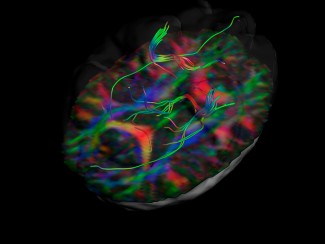

The team then used an artificial intelligence (AI) technique that analyses brain activity to extract information that usually escapes the human eye. In this case, AI helped the researchers to pinpoint the warning signs of a compulsive episode in the orbitofrontal cortex: an increase in slow brain waves, known as “Delta” waves.

Thanks to this signature of the coming crisis, the researchers developed a closed-loop neurostimulation system, which consists of briefly exciting the inhibitory interneurons upstream of the compulsions. It was a success: the technique allowed suppressing compulsive grooming in mice while reducing the number and duration of stimulations.

These advances could thus contribute to developing new neurostimulation therapies—which would be less energy-intensive than current techniques.

“Deep brain stimulation, which involves implanting electrodes to deliver a low-intensity electrical current in the brain, has already proved effective in treating severe obsessive-compulsive disorder—thanks to the pioneering work of Prof. Luc Mallet (AP-HP) and others,” explains Éric Burguière. “One of the obstacles to this technique is the need to replace the neurostimulator battery regularly. Our study opens the way to approaches that could reduce the need for surgery and make the treatment lighter and more personalised for the patient.”

Funding

This study was funded by the Fondation de France, the French National Research Agency and the Investments for the Future program.

Sources

Mondragón-González, S.L.*, Schreiweis C.; Burguière E. Closed-loop recruitment of striatal interneurons prevents compulsive-like grooming behaviors. Nature Neuroscience, Mai 2024. DOI : doi.org/10.1038/s41593-024-01633-3.