The acquisition of reading and writing are complex mechanisms whose subtleties we do not yet understand. Fabien Hauw and Laurent Cohen (Inserm, CNRS, Sorbonne University, AP-HP), neurologists at Paris Brain Institute, hope to uncover how we connect between sounds, words, letters, and their meanings. To do this, they study people who present an astonishing characteristic: they transcribe the speech of others into text, automatically and involuntarily. Catchy tunes on the radio, sensational statements on the news, confidences of a friend, meowing of a cat… These sounds will appear to them as imaginary subtitles floating before their eyes. After studying 26 people concerned by this particular type of synesthesia, researchers opened the door to a new world of language, as described in a recent study published in Cortex.

The anthropologist Francis Galton, Charles Darwin’s cousin, was interested in the most notable faculties of the human mind. In 1883, he observed that some people visualized the speech of their interlocutor in their internal mental space. “Some few people see mentally in print every word that is uttered […], and they read them off usually as from a long imaginary strip of paper, such as is unwound from telegraphic instruments“. The ticker tape no longer exists today, but this particularity – called tickertape synesthesia (TTS), remains.

Synesthesia is a neurological phenomenon in which different senses are stimulated simultaneously while processing sensory information. It allows some artists to hear colors, see sounds, or even taste music. In the case of TTS, synesthetes can read someone’s voice.

“This phenomenon goes far beyond the anecdote. It opens a window to understand better the mechanisms at work in processing written language and their neural bases,” explains Fabien Hauw, a doctoral student at Paris Brain Institute. He and Laurent Cohen, who co-leads the Neuropsychology and Functional Neuroimaging team, interviewed 26 people with TSS. Their goal? To find out in which conditions the subtitles appeared, in what form, and whether they could present an advantage or a handicap in everyday life. “We think that TTS occurs when the translation of phonemes into graphemes, i.e., sounds into letters, is too efficient,” explains Laurent Cohen. In these people, the connection between the mental representations of phonology and spelling is exaggerated, and the reading mechanism is somehow ‘forced’ as soon as they are exposed to vocal sounds.“

Indeed, even though this characteristic was described more than a century ago, it is still poorly understood. A previous study estimated that up to 1.4% of the population could experience involuntary subtitles when hearing a human voice, but this figure remains uncertain. It’s challenging to detect TTS subjects, who are generally unaware that they are distinguishable from the average person. “Several participants in the study were shocked to learn that not everyone has built-in subtitles,” laughs Laurent Cohen. We taught them through our recruitment ad. Like most forms of synesthesia, TTS is a subjective phenomenon. We don’t know how to measure it objectively, as we would evaluate visual acuity, for example. Nor is it associated with outstanding abilities or incapacitating cognitive impairments. This makes it an exciting but invisible quality.

A thousand transcripts

To better understand the subjective experience of tickertape synesthesia, Fabien Hauw, and Laurent Cohen asked the 26 participants, whose native language was French, to fill out a questionnaire. Indeed, many questions were left answered: can SST be triggered by a foreign language, new words, or noises (sneezing, meowing, motor humming)? Are the subtitles formatted in a specific way (size, color, capitalization, special characters) for each individual?

The researchers’ results indicate that for 73% of the participants, synesthesia appeared during the acquisition of reading in childhood. With almost half of them, this characteristic proved to be both an advantage and a nuisance; it helps them memorize words but disrupts their attention in crowded places where many conversations occur simultaneously. Indeed, for 70% of the participants, TTS is an automatic process that cannot be controlled.

Some synesthetes report that the appearance of the captions can be affected by the context of verbalization, especially when the speaker is emotional; the words may then change color or size, depending on the intensity of the emotion. “Letters may be blurred or shaking when I’m moved,” said one participant.

Even more surprising: some subjects report that when they watch a foreign movie, a second level of subtitles – a product of their synesthesia – appears above the subtitles embedded in the video. Others have subtitled dreams and nightmares, which provide their oneiric activity with a cinematic dimension. Finally, since one-third of the participants knew of other cases of TTS in their family, the emergence of this form of synesthesia might have a genetic basis.

Powerful super-readers?

In literate people, specific mental processes make it possible to interpret words, sounds, and letters and give them meaning. To be effective, these processes are fine-tuned under genetic and environmental constraints during development. Thus, we can observe a wide variety in reading performance across individuals, ranging from dyslexia…to synesthesia. In that sense, researchers believe that TTS results from a very atypical development of literacy.

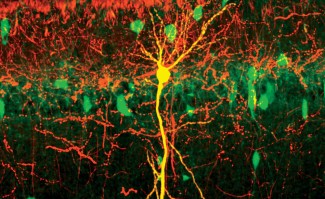

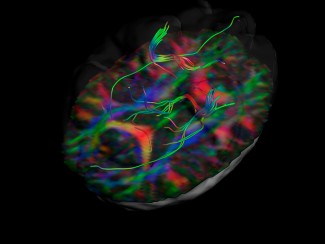

“In a previous MRI study, we showed that when a synesthete listens to a monologue, certain areas of the left hemisphere are activated more strongly than in a control subject, notably, regions responsible for speech analysis and a specific area involved in spelling – the VFWA (Visual Word Form Area),” Fabien Hauw explains. These areas are identical to those related to reading. The observations support the idea that tickertape synesthesia is a form of upended reading: instead of simply translating written words into sounds, these people automatically convert sounds into written words.”

The researchers’ observations must be reproduced with a more extensive and diverse sample of subjects. “Thanks to this study, we can map the spectrum of perceptions that exist in TTS. Now, we want to ensure that it is related to an overdeveloped access to orthographic representations“, says Laurent Cohen. We will never know if synesthetic scribes in ancient Egypt subtitled their interlocutors in hieroglyphics. But by illuminating the mechanisms of reading, we may be able to help children for whom this acquisition remains challenging.

Sources

Hauw, F et al., Subtitled speech: Phenomenology of tickertape synesthesia, Cortex,

Subtitled speech: Phenomenology of tickertape synesthesia - ScienceDirect

Galton, Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development, 1883.

Holm, T. Eilertsen, M.C. Price, How uncommon is tickertaping? Prevalence and characteristics of seeing the words you hear, Cognitive Neuroscience, 6 (2015), pp. 89-99, 10.1080/17588928.2015.1048209