The most severe form of epilepsy, status epilepticus is a high-risk neurological emergency. Yet its epidemiology remains poorly understood, particularly in France. By analyzing data from the French National Health Insurance system, compiled within the National Health Data System (SNDS), Quentin Calonge, Vincent Navarro, and their colleagues at the Paris Brain Institute provide unprecedented insight into its incidence, associated mortality, risk of recurrence after a first episode, and related risk factors. Published in Epilepsia and Neurology, this overview offers a new perspective on how this condition is managed and provides valuable guidance for organizing patient follow-up after hospitalization.

Status epilepticus refers to an epileptic seizure that does not stop spontaneously after several minutes. It is the most severe manifestation of epilepsy and the second most common neurological emergency after stroke. Its causes are highly diverse: intoxication, head trauma, infections, neurodegenerative diseases, tumors, and more.

This heterogeneity makes its epidemiological description particularly complex. Some patients require weeks of intensive care and suffer long-term sequelae, while others experience a more favorable outcome.

Until now, French data mainly came from expert centers or hospital-based cohorts. That skewed our observations toward the most severe cases and gave us only a partial view of the disease, particularly its actual mortality rate.

The First Nationwide Mapping of Status Epilepticus in France

To address clinicians’ questions, Quentin Calonge (AP-HP), neurologist at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, analyzed French National Health Insurance data from the SNDS as part of his doctoral research.

“The SNDS is a gold mine that remains largely underexploited. Yet it is one of the largest medical-administrative databases in the world, covering nearly the entire French population—almost 70 million people,” he points out. “It allows us to test, in real-world conditions, hypotheses drawn from international literature that are sometimes based on older or very specific datasets. For example, studies estimate an increase in disease incidence in certain countries, particularly the United States. But what about France, in everyday clinical practice?”

The researchers conducted an initial retrospective cohort study of all hospitalizations coded for status epilepticus between 2012 and 2022, including all types of care (specialized or non-specialized centers, intensive care or not, ICU or not, etc.). This approach enabled them to compare the trajectories of more than 118,000 patients—infants, young adults, elderly individuals, patients with or without preexisting epilepsy, and both severe and less severe cases.

Declining Incidence, Persistently High Mortality

Contrary to some hypotheses based on U.S. studies, the incidence of hospitalization for status epilepticus has been declining in France over the past decade. “That is good news, but its interpretation remains open,” cautions Prof. Navarro. “Is the disease truly becoming less frequent? Or are we intervening better and earlier, before seizures become prolonged?”

Mortality, on the other hand, remains high. In 2019, nearly 23% of patients died during hospitalization, and 36% died within one year of the episode. These figures remained generally stable over the decade, except during the COVID-19 pandemic. The saturation of intensive care units was accompanied by a decrease in intensive care admissions for these patients.

“We are seeing an increase in mortality among those who were not admitted to intensive care, suggesting a loss of opportunity linked to less specialized care,” says Prof. Vincent Navarro. “Notably, this excess mortality persisted through 2022, even though intensive care bed capacity has returned to normal, raising questions about possible lasting changes in admission criteria.”

Better Defined Causes and Risk Factors

Any attack on the brain can trigger status epilepticus. It is therefore essential to carefully distinguish between acute concomitant causes of status epilepticus (such as a stroke with complications), progressive causes (a growing brain tumor), and remote causes resulting from prior injury (for example, an old head injury that left residual lesions). Reconstructing these medical histories required meticulous work.

The researchers conducted a second retrospective study involving nearly 52,800 patients between 2011 and 2016. Of these, approximately 38,000 survived their initial hospitalization for status epilepticus and were followed for three years. By cross-referencing data on hospitalization, healthcare reimbursements, long-term conditions, and death certificates, the team estimated underlying causes, precisely measured recurrence rates, and analyzed causes of death.

Their findings highlight a high prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases in elderly subjects—up to 30%. “In a way, neurodegeneration paves the way for status epilepticus,” summarizes Quentin Calonge.

When the episode is linked to an acute cause, such as stroke, meningitis, or head trauma, the risk of death is particularly high during hospitalization. However, once the critical phase has passed, these patients do not show any increased long-term mortality compared to the rest of the cohort.

Late mortality, by contrast, is mainly driven by cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and infections—the same leading causes observed in the general population. Status epilepticus thus appears more as a marker of overall vulnerability than a direct cause of death.

Better Anticipating the Risk of Recurrence

Discharge from the hospital is often perceived as an end, when in fact it marks the beginning of a high-risk period. Data show that about 17% of patients experience a recurrence within three years, and this risk can be identified upon discharge.

Progressive neurological conditions—such as brain tumors, neurodegenerative diseases, or neurometabolic disorders—significantly increase the risk of recurrence, as does the number of associated comorbidities. These findings can guide the organization of follow-up care and therapeutic education programs, particularly for patients with preexisting epilepsy.

More surprisingly, the recurrence rate reaches 21% at 3 years among young patients, compared with around 15% in adults. “This finding goes against our clinical intuition,” notes Prof. Navarro. “It shows how compartmentalized our practices remain between pediatric, adult, and geriatric neurology, and how much population data is needed to break down these silos.”

By combining national data, longitudinal follow-up, and in-depth statistical analyses, this research shifts the focus on status epilepticus, which not only requires emergency intervention but also raises questions about patients' medium- and long-term trajectories. These results open up new avenues for research and provide concrete levers for improving care: identifying the highest-risk patients, adapting post-discharge follow-up, and better targeting therapeutic strategies where they will be most effective.

Sources

Calonge, Q., et al. Recurrence and mortality after a first status epilepticus. Neurology, June 2025. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000213693.

Calonge, Q., et al. Incidence, mortality, and management of status epilepticus from 2012 to 2022: an 11-year nationwide study. Epilepsia, September 2025. DOI: 10.1111/epi.18627.

Image

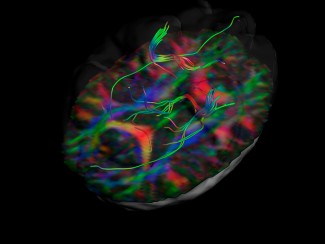

View of the white matter fibers of the uncinate fasciculus in a patient with temporal lobe epilepsy. Credit: Christopher Whelan, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

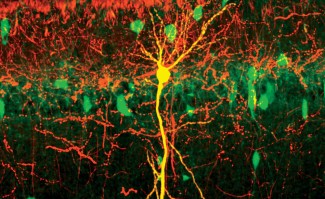

The team "Clinical and experimental epilepsy" explores how the brain becomes epileptic (epileptogenesis), how it produces seizures (ictogenesis) and the relationships between neurophysiological activities and clinical semiology. The team is also...

Read more

Epilepsy

The word ‘epilepsy’ originates from a Greek word meaning ‘to seize’, reflecting the sudden and unpredictable onset of seizures. In France, 600,000 people are affected by this chronic neurological disease, which can present with different symptoms...

Read more